While reading along in The Art of Torah Cantillation (link) one stumbles upon the claim ( page 13) that one is encountering a list of the five of the most common variations of the etnachta clause (or clauses ending with the ‘enachta’ cantillation mark) in the Torah/Pentateuch.

The first pattern of the clause given on page 13 is:

‘Mercha, Tipcha, Munach, Etnachta’

You might wonder just how common the above pattern is and should you spend your time committing this pattern to memory or not? Great question but how does one go about answering such a question. In time past you would need to simply trust the authors’ judgment, scan through the Bible counting count all the patterns, or consult a concordance of the accents. Today, however, there are two currently available commercial software programs Accordance and now Logos as of 2019) that are capable of running searches on the cantillation marks and their patterns and there used to be a third program (BibleWorks) but it is no longer available for purchase.

While the three programs mentioned above are capable of running such queries Accordance Bible Software is my program of choice for the following reasons:

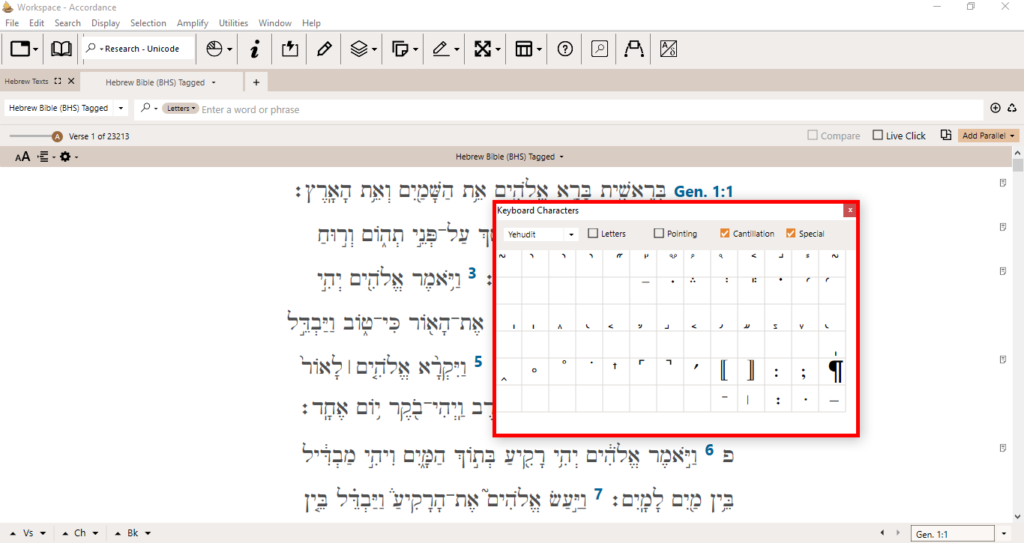

(1) Searches in Accordance are visually intuitive and quick to set up. You simply open the ‘character keyboard’ and click on the accent or accent marks you want to search on. No need for codes or esoteric program like language to run searches. The first program I used to run such searches BibleWorks required me to type in codes for each accent on the command line making searches time and energy-consuming to set up. At the time I was very thankful to be able to run such searches. Then when I tried Accordance and it was like a breath of fresh air there was no turning back.

(2) budget-friendly. If you already have a Hebrew text in Accordance you can run accent searches. No need to buy extra modules, database or dataset to run searches.

(3) bugless, glitchless, and almost error-free. Because Accordance was the first program to implement accents searches (back in 2003 with verse 6) they have had the time to work out almost all the issues over the years.

The Interface. Okay, I know this is very subjective! But I find the interface to be so intuitive that not only does it not get in my way, I almost completely forget about the interface while using the program.

Now, back to the question:

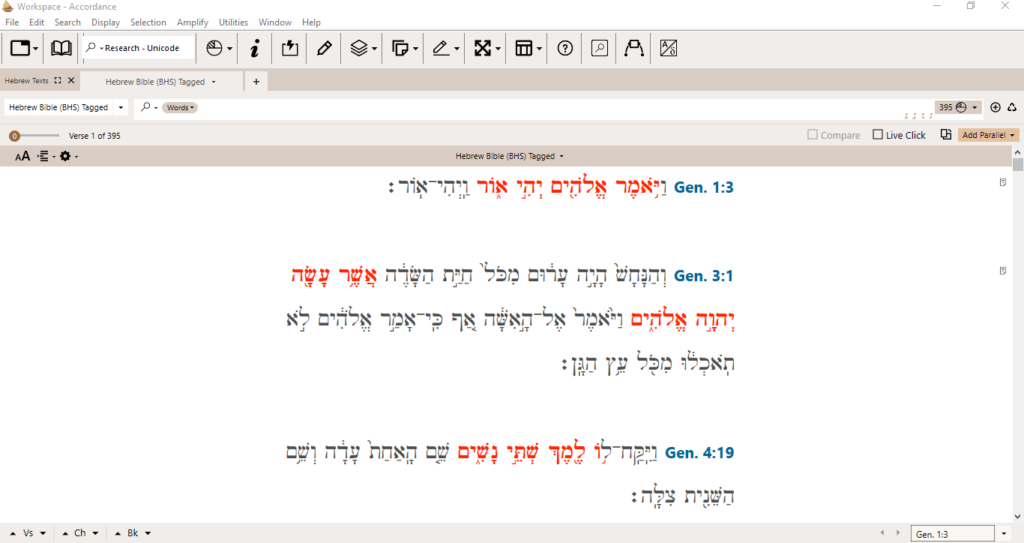

How common is the accent pattern: Mercha, Tipcha, Munach, Etnachta’ ?

in Accordance, the names are slightly different Merka, Tiphah, Munah, Atnah but it doesn’t matter as one does not need to type in the names all one needs to do is right-click on the visual representation of the accent(s) one desires to search on.

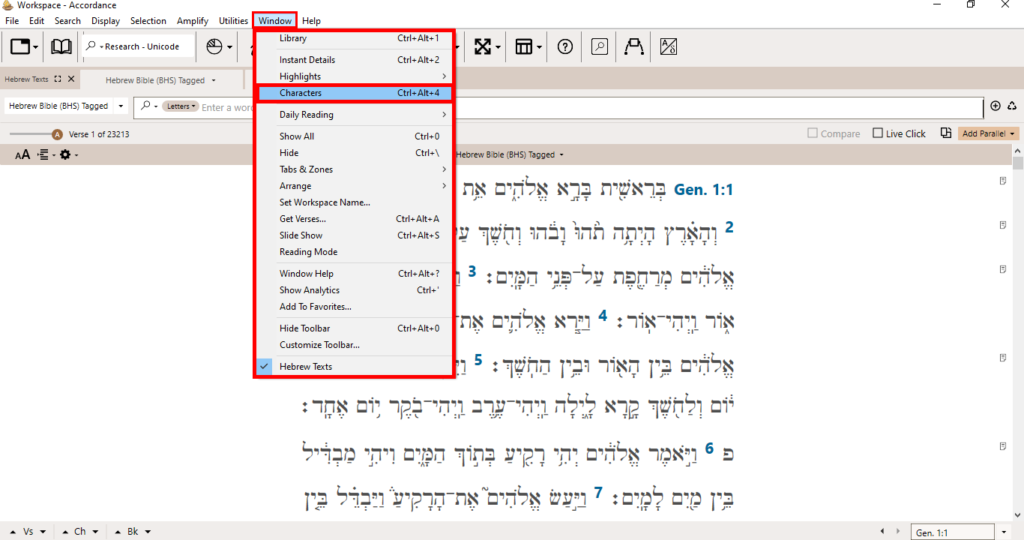

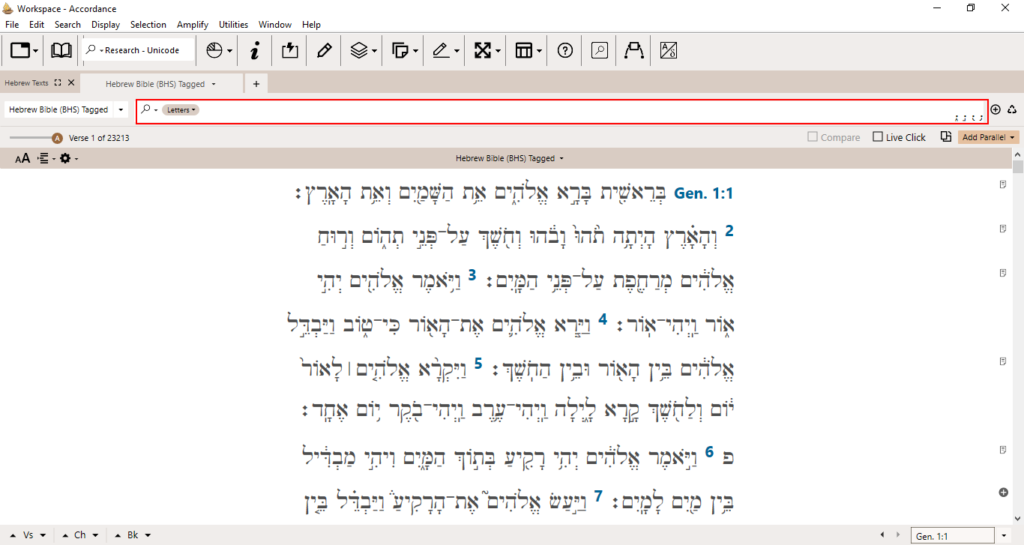

In Accordance Bible Software version 13 one would first need to open the program and a Hebrew Text of course. Then they would need to click on ‘Window‘ on the ‘menu bar‘ and on the drop-down menu select the option Characters.

After which the ‘Character Keyboard‘ (formerly known as the Character palette ) should appear.

Then in the search entry area simply type in a period before each clicking on each accent you would like to run a search on. (The period acts as a wildcard or place holder for a character in this search). If one is searching for an accent clause or pattern one needs to click the space bar between each period accent combination.

Then hit the enter button to run the search.

This search returned with 395 verses.